How fitting is it that the last blog post I’m writing for my undergrad career at SPU is one about designing for good. I remember writing my application essay to the major my spring quarter of my freshman year, and saying that I wanted to use design as a means of change. I laugh back at that because I had NO idea the implications of that. My idea of design at that time was so much based in visual form, not in thinking. Somehow I thought perfectly kerned type (not that I could even properly kern at that point) was the way I was going to change the world. I can only laugh at that now.

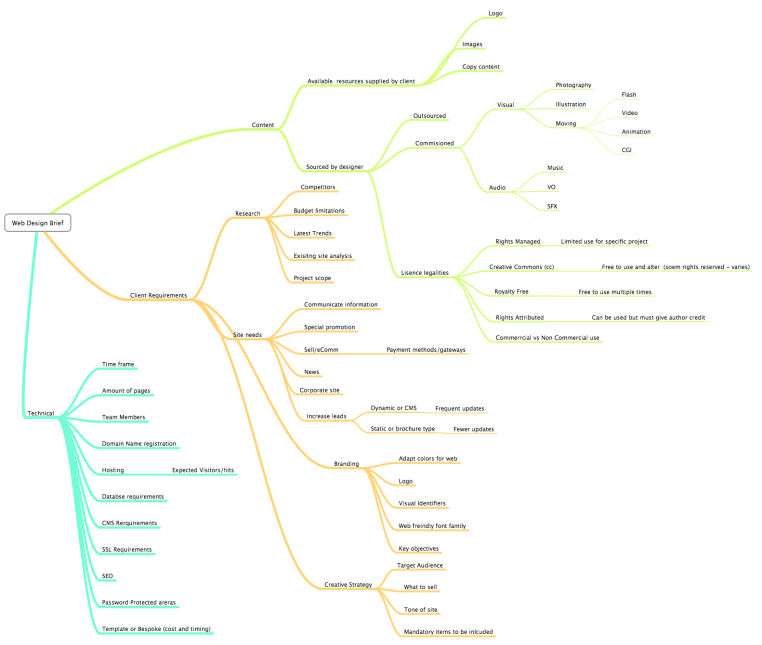

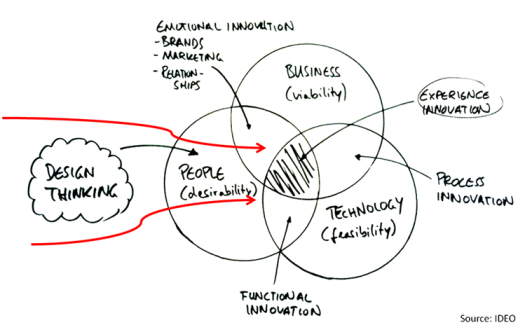

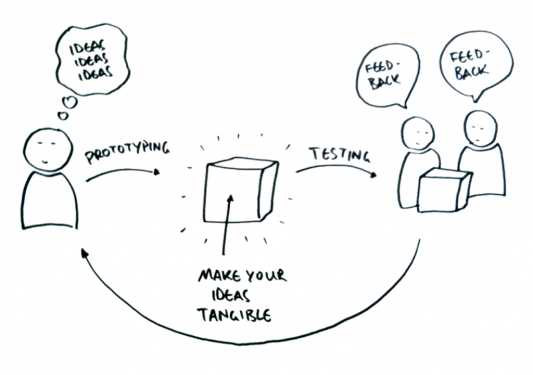

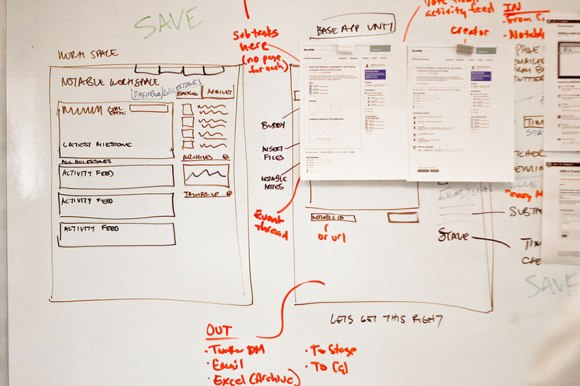

But now I understand that designing for good is much more of a thinking process than a visual process. It means finding a need, a passion, something that you desperately want to be involved in, and researching it. Prototyping a solution. Researching again. Prototyping again. Gathering feedback. Revising, revising, revising, all to come to a solution that addresses a problem or a need in the most coherent way possible – which doesn’t always mean the most jaw-droppingly beautiful. Design thinking is without a doubt a way to engage the culture.

It’s my hope that as I transition into a career, I’m able to focus my work on this kind of process. I want to be an intelligent creator. I want to constantly ask questions. I want to constantly be engaged with other people who are also constantly asking questions. I want to be a part of an industry that aims to problem solve to find the best solutions. And I’m hopeful that I will be able to do just that.

But most of all, I just never want to stop learning, because I don’t think it’s possible to design for good without pursuing understanding as well.

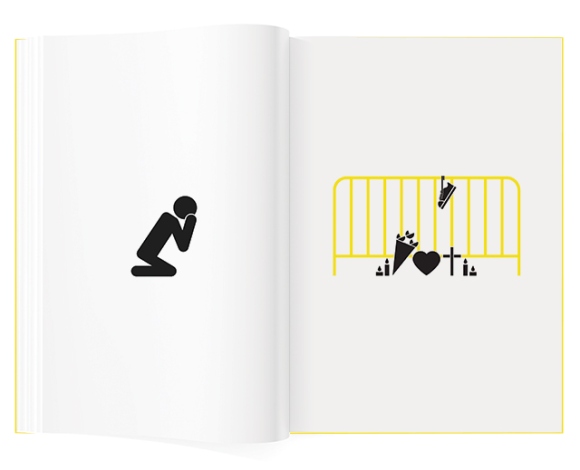

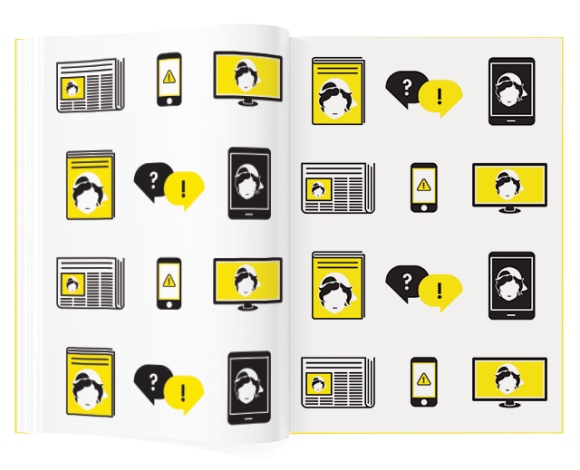

One of the Design for Good examples on AIGA’s website that resonated with me especially was an iconographic book telling the story of the Boston Bombing, entitled 102 Hours, by Tank Design Inc. Maybe it’s because we’re so close to June 5th, and that makes me especially responsive to this kind of storytelling, but there was something in the universality of the symbols they used that made this feel like a collective story – that we were all in this grief thing together. And there’s something really, really powerful in that. Sometimes design is a process for your own healing, and sometimes it’s for collective healing. And I’d say that’s definitely Design for Good.

source: http://seattle.aiga.org/designforgood/